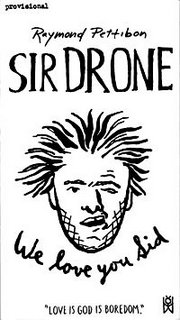

Sir Drone * Raymond Pettibon * 1989

In 1989, artist Raymond Pettibon shot four movies on home video equipment: Citizen Tania, Weatherman ‘69, The Book of Manson, and Sir Drone, a chronicle of the trials and tribulations of two nascent punk rockers in late 70s L.A. as they struggle to not be posers.

Duane and Jinx—played by Mike Watt of the Minutemen and fIREHOSE, and artist and one-time member of Destroy All Monsters Mike Kelley, respectively—desperately want to start a punk band. They sit on the floor of their sparsely decorated apartment playing inept, discordant noise not unlike that of early Half Japanese (I have to hand it to them—it’s not easy to fake such musical incompetence, as the two actors are actually talented musicians). Jinx in particular doesn’t know how to play “real” chords, making them up instead, which never ceases to infuriate Duane, whose ideas of what a punk band should look and sound like are quite rigid. Jinx, while naïve and insecure and thus all too willing to follow Duane in his quest to embody this strict punk rock image, seems like the visionary of the two.

The film, one might say, is about posers desperately trying not to be posers. In one scene Duane randomly yells out his window, “Hey, you poser!” When Jinx asks who he’s yelling at, his response is “Just some poser.” He then grabs a radio and holds it out the window, claiming he’s going to throw it at a hippie, but can’t bring himself to do it. He wants to act outrageous but doesn’t have the guts.

The film, one might say, is about posers desperately trying not to be posers. In one scene Duane randomly yells out his window, “Hey, you poser!” When Jinx asks who he’s yelling at, his response is “Just some poser.” He then grabs a radio and holds it out the window, claiming he’s going to throw it at a hippie, but can’t bring himself to do it. He wants to act outrageous but doesn’t have the guts.At a show, they run into Duane’s cousin, Vince. (“I’m not Vince anymore, Duane. Call me Gun.” “I’ll call you an asshole before I call you Gun.”) Apparently Vince is a punk now, and they invite him back to their apartment and later to sing in their band. Now all they need is a drummer to complete their quartet, so they audition various people who seem wholly unimpressed. When the particularly arrogant Bizz attempts to play along with the other three, he scoffs at Jinx’s guitar playing: “Man, my sister can play better than that!”

Things really start to go downhill when Jinx brings home a girl named Goo* and Duane gets a little jealous, tension heightening in the household. Jinx quits the band several times, despite the fact that he’s still playing music with them.

The auspicious moment arrives when Vomit, played by Raymond Pettibon, shows up looking for Bizz, and mentions that he has an open time slot at a gig he’s setting up. A drawn-out “harrowing” scene follows—I won’t ruin this part but it involves scissors.

The film ends on a cheerful note, the band playing as a four-piece with Goo on drums, the final shot a hand-drawn Pettibon flyer for an X/Germs/Dils/Punktones/Sir Drone show.

While the characters can be gratingly annoying, they’re also strangely endearing. The dialogue is brilliant and at times hilarious, my favorite line occurring when Vince holds up some Peter Frampton records and asks who they belong to. Duane, mortified, says, “all that shit belongs to Jinx,” who replies, “I play ‘em at 78, man!” Another great moment comes when the band is trying to come up with a name. The rejected suggestions include Neutron Bomb, The Glue Snifters, Acne Condom (“I like that one, but not for our band”), Gigantor in Bondage, Chairman of the Bored, The Men From Punkle, Revoltin’ Travolta, Summer Picnic Nightmare, and The Jacket Offs, among others.

On the surface, the film appears to be making fun of punks, though I think the theme is a little more complex than that. Like anything of its kind, the punk scene spawned more than a few Johnny-come-latelys who turned it into a parody of itself, and perhaps Pettibon was trying to portray these negative aspects. Or maybe he just wanted to tell the story of two young, insecure, awkward kids who want so badly to be punks that they forget to be themselves.

* I wonder if Goo is named for the Sonic Youth song “My Friend Goo,” the title character a girl who plays the drums and “looks through her hair like she doesn’t care.” The fact that Raymond Pettibon drew the cover art for Goo seems to reinforce this theory, though I can’t be certain.

No comments:

Post a Comment